Tech for Parks:

Vulcan EarthRanger

Technology is playing an increasingly important role in conservation. But as the availability of technology increases, so does data management complexity.

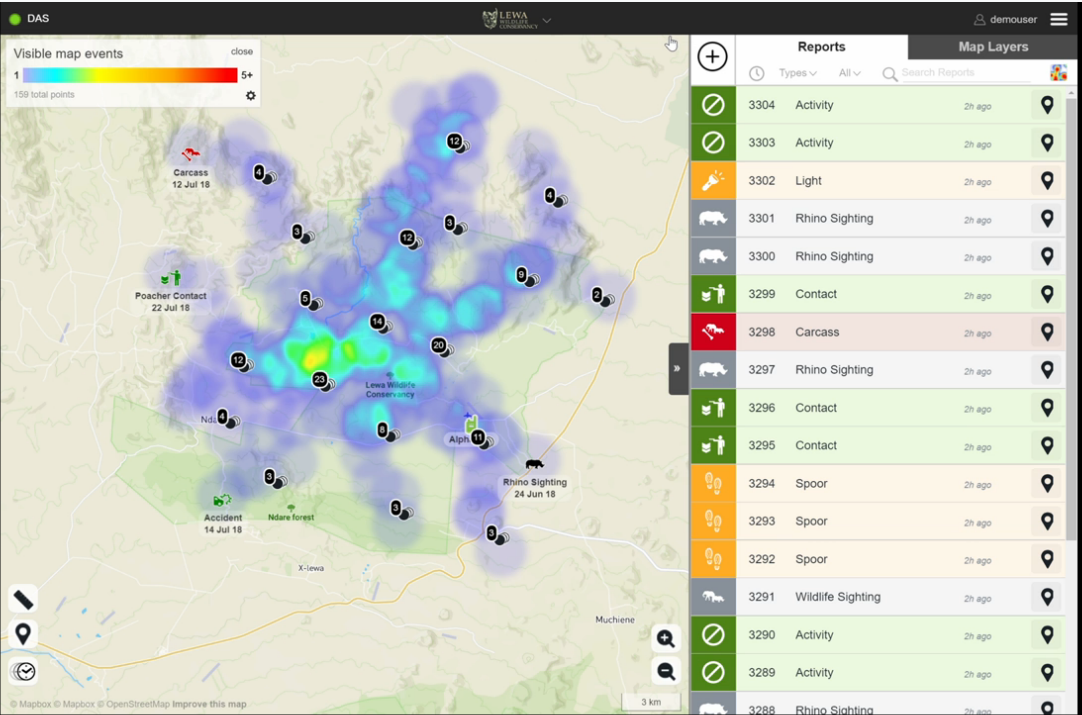

How does a conservation manager integrate a surge of incoming information from animal GPS collars, cellular trail cameras, field locations of snares from rangers on patrol, drone imagery, and satellite data in the most efficient way possible?

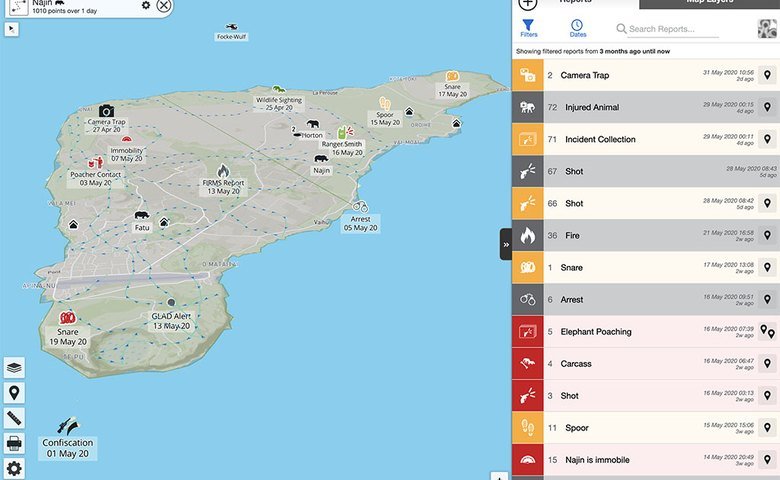

Vulcan EarthRanger solves that problem. EarthRanger is an easy-to-use online software platform that collects, integrates, and displays all available historical and real-time data from a given protected area. The software combines all of this data into a single, continuously updated map, so that managers can monitor the ecosystem, anticipate potential poaching threats or human-wildlife conflict, and react to ongoing threats in real-time.

“[Protected area managers] were feeling overwhelmed by [data] and couldn’t use it effectively,” said Ted Schmitt, a long-time Vulcan business developer. He explains that before EarthRanger, operations rooms contained multiple screens, each displaying different data, which were impossible to watch all at once. Even when they could monitor incoming information, it was difficult to visualize patterns between different data sets.

Consequently, Schmitt and his team created EarthRanger as a “one-stop data hub” that integrated multiple data streams that used to be housed on separate devices. This gives managers a complete picture of their protected area in real time, allowing them to more quickly deploy ranger teams in response to a threat. They can also use EarthRanger to analyze patterns, helping them to anticipate crimes and apprehend poachers before an animal is killed.

“It’s the most important tool,” Wesley Gold, law enforcement manager for the Grumeti Fund, which protects wildlife in the Serengeti, told GeekWire. “I’m sitting here in Seattle, and I’m logging on and checking what’s going on back home. If I see anomalies, I can get on the phone and say, ‘Sort that out.’ ”

"We are now able to focus on interdiction rather than just response,” he says, “That’s how wildlife numbers go up."

Some examples of EarthRanger's capabilities:

Managers can monitor multiple wildlife GPS collars and send alerts when an animal wanders out of the reserve or close to a village, allowing them to intervene when necessary and help communities to better co-exist with wildlife.

Use computer vision and machine learning to tally the number of animals in photos captured by drones.

Law enforcement officials can track their ranger teams through GPS-powered walkie-talkies and accurately direct them to the location of suspicious activity.

Comprehensive visualization allows officials to track patterns that inform their patrol deployments – positioning themselves a step ahead of poachers.

Ecological monitoring, which betters scientists understanding of the ecosystem’s health, helps answer questions like, “How should we respond if there's a drought?” and “What does the ecosystem need to look like if we want to reintroduce rhinos?”

Outreach and education events can be input in EarthRanger, and analyzed in terms of how public programming impacts poaching numbers.

EarthRanger helps managers figure out how to allocate their resources most efficiently to stop poaching and human-wildlife conflict. For national parks and protected areas that are often short on funds and staff, this “force multiplier” effect is crucial.

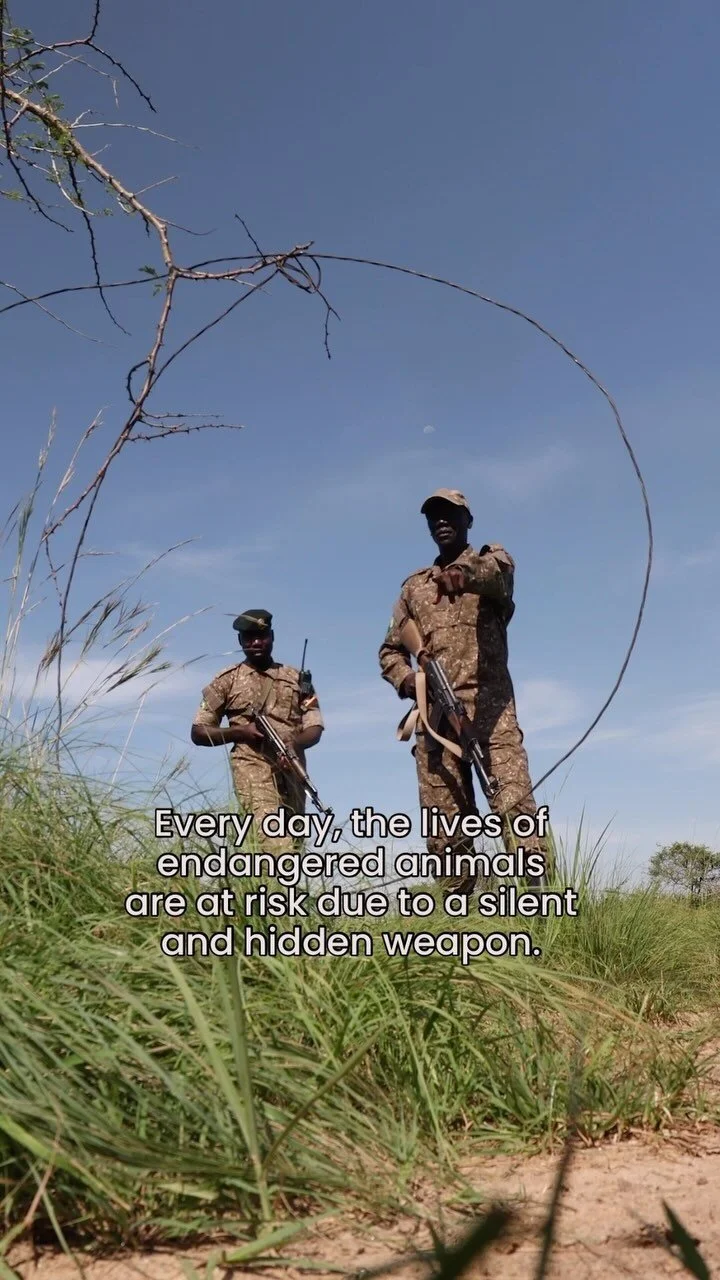

"You’ll never get away from needing boots on the ground," executive director of the Grumeti Fund Stephen Cunliffe told Geographical, "but technology can make sure those boots on the ground are in the right place at the right time."

Game scout Gotera Gamba of the Grumeti Game Reserve in Tanzania told Reuters that EarthRanger has made rangers’ work easier and more efficient, saving the lives of both wildlife and rangers, who regularly lose their lives to poachers.

“Previously our job was very difficult because, for example, if you got an alert it would take a very long time before you go out to respond as you had to note it on a notebook, and rigorous communications with the radio room.”

EarthRanger data comes from, among others:

Ranger-recorded observations directly from CyberTracker-SMART Connect

Radio systems with data transmission and GPS-tracking capabilities

Animal collars

GPS trackers in contraband, like rhino horns or illegal timber

Informant information

Spatial data layers that give geographic context, like hydrology, human infrastructure, and forest cover

Sensor data from camera traps

Vehicle sensors

Drones and remote sensing images from satellites

EarthRanger was developed by Vulcan, the company founded by Microsoft co-founder, tech pioneer and philanthropist Paul G. Allen.

Vulcan is committed to improving our planet and changing the trajectory of some of the world’s most difficult problems, and are perhaps best known for funding and coordinating the $7 million 2014 Great Elephant Census. The Census was the first pan-African survey of savanna elephants in over 30 years, conducted to help understand the current state of African savanna elephants. The census showed 352,271 African savanna elephants in 18 countries—a 30% population decline in just seven years. That census, in part, inspired EarthRanger, which now helps to keep elephants safe.

The data are stored in a secure cloud platform and readily accessible to visualize through the EarthRanger web app, an iOS app, Google Earth or to be downloaded for further analysis within GIS software. A total of 20 locations worldwide are currently using EarthRanger, and since its first deployment in 2017, rangers and park managers have used EarthRanger to log more than 32,000 security reports, remove more than 13,000 snares and make more than 1,170 arrests.

In 2017, the black market price of ivory was about $725 per kilogram ($329 per pound) – making each individual elephant tusk worth $50,000 on average. Shana Tischler, Vulcan’s strategy manager for ivory trafficking, explains that poachers typically camp out for the duration of the rainy season, when it's harder for rangers to conduct patrols. One piece of ivory is worth it, providing an African family financial support for a year.

EarthRanger is a critical tool in battling ivory poaching. The technology allows protected area managers to identify poaching hotspots, watch elephant movements, and predict poaching events, helping to save the lives of these gentle giants. With the help of EarthRanger, conservation managers and law enforcement in Kenya's Masai Mara reduced elephant poaching incidents from 96 deaths in 2012 to just four in 2018, making 354 arrests of poachers during that time.