Radars Against Illegal Fishing: How the technology-community partnership works to protect biodiversity in Baja California Sur

Updated 06/30/25By Astrid Arellano – Originally published in Spanish on Mongabay Latam.

On the east coast of Baja California Sur, a radar system seeks to curb illegal fishing and poaching of marine species that impact national parks and fishing refuges. In this region of northwestern Mexico, a partnership between organizations, community guards, park rangers, and the government patrols and monitors the area using technological tools such as drones and long-range surveillance cameras.

“We started with Cabo Pulmo National Park, where the first Marine Monitor (M2) was installed. This is an integrated system of cameras and radars that allows park rangers to expand their surveillance capabilities through technology,” explains Alejandro González Leija, oceanologist and director of Global Conservation in Mexico, an international organization that leads the Global Defense of Parks initiative in partnership with the Mexican organization Pronatura Noroeste and the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Conanp). The goal is to strengthen networks of community fishing refuges and no-fishing zones within national parks.

Although the problem of illegal fishing of various fisheries resources in protected areas of Baja California Sur varies from one area to another, from Cabo Pulmo to Loreto Bay National Park, illegal fishing for finfish has been common. In this region, industrial fishing—such as for shrimp or tuna—is prohibited, so when such vessels are detected, alarms are activated and authorities are coordinated to monitor them.

The scope achieved with that first phase of the initiative in Cabo Pulmo, carried out more than ten years ago, served as an example for replicating the model in Loreto—in a much larger territory—and other areas such as San Basilio Bay, the San Cosme-Punta Coyote Marine Corridor, and the Islas Marías Biosphere Reserve.

Bigeye trevally jacks form a bait ball tornado with a diver in Cabo Pulmo National Park.

“The first thing we began to see was a decrease in navigation patterns indicating suspected illegal fishing in Loreto. For instance, the number of vessels showing a pattern of suspected illegal fishing dropped from 100 to just 10 in a month,” describes Sergio González Carrillo, former regional coordinator of Pronatura Noroeste and site leader in Magdalena Bay, who has worked on the radar project since its inception.

González Carrillo explains that the fishermen stopped entering the national park when they realized they were under observation. “That's very valuable because as organizations, we want to support the authorities, and our role is to try to deter these illegal activities, which have decreased significantly. That's very powerful data for us,” he says.

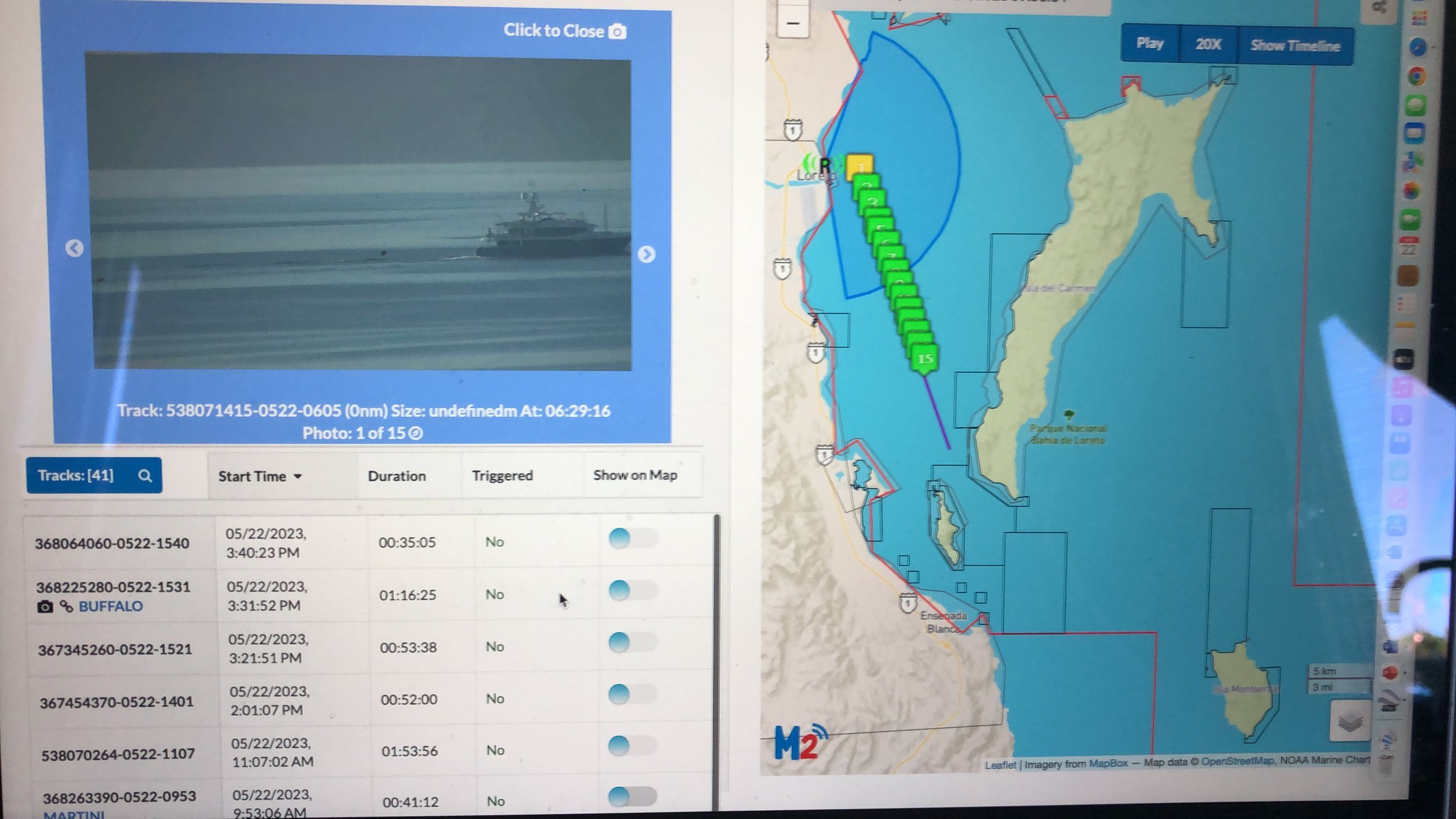

These radars can track navigation patterns and speed up to 15 kilometers from the coast. They not only detect large vessels carrying automatic identification systems (AIS)—designed to provide satellite-based information such as their position, speed, and heading to other vessels and coastal authorities—but also those not required to carry these devices, such as yachts, sailboats, smaller sport and commercial fishing vessels, and even kayaks. They also provide information of interest regarding other unregulated activities in protected natural areas, such as tourism.

The radar system configures polygons of interest with specific parameters that generate automatic alerts to notify park rangers of suspicious activity, allowing them to verify it in real time using the system or the camera. Historical information is also stored for review and analysis, complemented by regional tools such as Skylight and Global Fishing Watch for broader monitoring.

A fin whale swims across the calmed sea of cortez in Loretto Bay National Park. Photo ©shutterstock.com

Pressures on Loreto Bay

Loreto Bay National Park is one of the most important protected natural areas in the country. It was declared a protected area on July 19, 1996, and covers approximately 206,581 hectares. Due to its ecological significance and biodiversity, it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005 and as a Ramsar Site in 2004.

The presence of more than 1,300 species of flora and fauna has been documented, including 30 species of marine mammals and 38 species of endemic plants and animals. Blue, fin, and humpback whales are prominent in its waters, where they share habitat with orcas, dolphins, sea lions, and sea turtles, as well as 17 species of seabirds.

The national park allows fishing activities in specific areas under controlled conditions. Fishermen must use only selective fishing gear that minimizes environmental impact and the bycatch of non-target species, i.e., those with no commercial or food value, such as juvenile fish or protected species like sharks and turtles. In 2019, its Management Program was modified, increasing the area where fishing is not permitted from 108.4 to 6,219.3 hectares.

Despite these measures, the area faces constant pressure from illegal fishing, overfishing, and the rise of unregulated tourism activities, the detection of which is difficult given the large area.

“Fishing areas are distributed throughout the national park, and this represents a challenge, first, to protect these areas and, second, to ensure that fishing is carried out with the correct permits, vessels, fishing gear, and mesh size. This requires not only technology but also the presence of inspectors in the area,” explains Alejandro González Leija.

Sharks being inspected by a fisheries officer at Loreto Bay National Park.

Pronatura Noroeste says that even though there are laws to punish illegal activities and many efforts are made by park management, Mexican environmental authorities and organizations monitoring Baja California Sur's protected areas are not very effective because there aren't enough tools, budget, or staff to quickly find illegal activities.

"How can we ensure that field personnel or inspectors are there? Well, we need more. Baja California Sur only has seven or eight inspectors to cover the entire state. Furthermore, Profepa [Federal Attorney General's Office for Environmental Protection] inspectors don't just look at the sea but also at the land," says Sergio González Carrillo.

In the specific case of Loreto Bay National Park, in addition to the radar system, the organizations set up a working group to develop a manual for handling illicit activities.

"It's the first of its kind and involved more than ten authorities. Thanks to this manual, even with staff turnover, the procedure remains consistent, which facilitates training and work continuity. Furthermore, surveillance patrols have been increased," adds González Carrillo.

Fisheries surveillance committees in the community of Agua Verde, Baja California Sur.

Vigilant Communities

Illegal fishing is driven by several factors, experts agree. Curbing it requires not only technology and the presence of authorities but also, for example, legislative changes and a strengthening of working arrangements with fishing cooperatives.

"It's essential to properly trace the origin of the product and ensure it comes from responsible and legal fishing. Furthermore, we must understand the factors that drive illegal fishing," says Alejandro González Leija.

There are fishermen who are not criminals, the oceanologist affirms, but rather people "who have tried for years to obtain a permit to fish legally, but for reasons beyond their control have been unable to access that right. That part of the problem also needs to be addressed," the specialist adds.

Therefore, the team works with local communities and fishermen to protect biodiversity and their livelihoods, actively involving them in decision-making. They have established committees made up of community members to support surveillance and monitoring of illegal fishing activities. They have trained the community members in the use of radars and the surveillance system. Locals familiar with the area comprise these committees, enabling them to identify suspicious activities.

Sea cucumbers are among the most commonly poached animals.

Additionally, there is a partnership with landowners to install Mobile Marine Monitors (M3s), which offer greater autonomy by operating with a renewable energy source and a mobile trailer, allowing them to be deployed in hard-to-reach locations without a power grid connection. These radars also serve to monitor the presence of poachers in marine protected areas, while landowners are involved by disseminating good fishing practices.

In the southern area of Loreto Bay National Park, this tool has proven to be a technological advantage for understanding nautical and fishing activity, as well as representing a valuable instrument for the fisheries surveillance committees of nearby cooperatives in the communities of Agua Verde and San Cosme.

"Things are going well because the interest is such that they say, 'You set up the radar, and we can provide boats and gasoline to go out and respond to what the radar indicates, in addition to training ourselves to file reports.'" They understand that all these actions are ultimately about protecting the resources they themselves are protecting," describes Sergio González Carrillo.

However, patrolling is not a simple task. Organized crime often finances illegal fishing in search of high-value species on the black market, such as the critically endangered totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi), coveted for its swim bladder, which is used in traditional Chinese medicine. Therefore, efforts are being made to strengthen relations with the Navy and other authorities that can protect the team, which includes park rangers, community guards, organizations, and inspectors.

“We've had safe spaces for the installation of these systems, but there are also people whose interests are affected. These are usually those who aren't aligned with legal fishing activities. Finding the conditions for the deployment of this technology has its challenges,” says González Leija.

Coastal patrol of the Secretariat of the Navy (Semar) in the Marías Islands.

The Future of Marine Protected Areas

In Latin America, the same system has been installed in national parks in Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, and most recently in Panama, in April 2025, in Coiba National Park.

In Mexico, Global Conservation will expand its presence in other regions of the country at the request of Conanp. The Banco Chinchorro Biosphere Reserve is one of the potential sites of interest for the organization, where illegal fishing of species such as lobster and snails occurs. Therefore, Global Conservation conducted an initial survey and outreach visit to the reserve in March 2025.

The Banco Chinchorro protected area contains nurse sharks that swim along the coral areas. Photo ©shutterstock.com

This reserve is located off the coast of Mahahual, in the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo, and represents one of Mexico's most outstanding protected natural areas. With its 144,360 hectares, it is the largest coral atoll in Mexico and the second largest in the world. It was declared a protected area in 1996 and is recognized for its exceptional biodiversity and ecological value.

"We are currently waiting to sign the national agreement, which will provide us with a more solid foundation to begin exploring areas of interest, including Banco Chinchorro. The idea is to establish work plans, if the reserve also deems it of interest, and move forward along those lines," adds González Leija.

Illegal fishing not only affects marine biodiversity and fishing communities but also consumers in cities who must remain vigilant, says Leija.

“Illegal fishing has a cultural impact on the communities that depend on this activity and are proud to be fishermen, and we celebrate that,” the oceanologist concludes. “That's why it requires a multi-pronged effort—including the legislature and authorities—and for the sector itself to understand that carrying out legal fishing will benefit us all, but primarily them.”

More GC News related to Baja:THE BAJA SUR CALIFORNIA MEXICO MARINE PROTECTION 2023-2024 IMPACT REPORT

March 21st, 2025 UPDATEThe first-ever Mobile Marine Monitor (M3) was deployed in Mexico. The M3 provides accurate information regarding vessel loitering and sailing navigation between Loreto and the marine corridor and triggered > 2900 alarms in 2024.

Baja Sur California has become highly threatened in the past 5-10 years, with many community fisheries on the verge of collapse, diving operations no longer profitable and key species like hammerhead sharks having vanished from this critical marine ecosystem.

After years of exploitation by mainland industrial fishing fleets, Baja Sur California needs recovery and protection from unchecked industrial fishing, which has largely denuded the underwater wonderland that is Baja Sur, leaving ghost nets and long lines across the UNESCO World Heritage site, one of the world’s most important marine ecosystems.

Neither the three National Parks or CONASPECA, the Commission for Fishing, with whom we work daily, have had sufficient resources—boats, wardens, law enforcement, and fisher community liaisons—to fight back against the increasing pressures and stem species extinction and economic collapse of fishers and diving operators, a once-thriving tourism sector.

Shark fins lay on a pile of netting. Photo ©shutterstock/Tara Lambourne

Illegal fishing, shark finning, industrial fishing now controlled by cartels, and heavy sports fishing are all threatening Baja Sur California Eastcape and extinction of entire species.

Focused on the UNESCO World Heritage site of Baja Sur California and its Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Community Fisheries, Global Conservation is focused on four critical areas of Marine Protection for Baja Sur California:

Real-time Surveillance—now three (3) marine radars 24/7 monitoring

Increasing Rapid Response—Patrols have nearly tripled in 3 years

Joint Conapesca Operations—first time integrated patrolling with Fisheries Ministry

Funding the above activities with our key Partners in Conservation

This impact report covers 2023-2024 progress and outlines the challenges ahead for our Marine Protection work in Baja Sur, California, Mexico.

GC has deployed multiple Global Park Defense (GPD) systems for Marine Protection beginning in 2020 focused on the Eastcape of Baja Sur from Loreto Bay National Park in the north to San Jose Island and Espiritu Santo National Marine Park off La Paz. As well, GC Mexico works to protect community fishing reserves from Agua Verde in the north to Boca Del Alamo in the south.

Global Conservation's primary objective is to safeguard the endangered marine ecosystems of the Baja California Sur Marine Corridor (BSMC) by reducing the pressures of illegal fishing (artisanal, sport, and industrial). Our strategy involves collaborative efforts with national parks and fishery authorities, communities, and NGOs to support them and enhance their capacities to combat IUU fishing.

The M2/M3 radars are capable of capturing live images of vessels a few miles out form the coastline.

Global Park Defense has proven to be an effective, flexible, and robust methodology for Marine Protection that combines technology, knowledge and expertise, and a network of 24/7 real-time marine radars with specialized software to remotely survey large areas with integration to Skylight and Earthranger, improving the effectiveness and frequency of targeted marine patrolling and Rapid Response Teams combined with Community Protection.

After four years, GPD has now been adopted by the Mexican authorities across the Baja Sur Marine Corridor. We are investing in the technical and patrolling capabilities of the collaborative relationships built with all key government partners—CONANP, SEMARNAT, SEMAR and CONAPESCA; Park Authorities, communities; NGOs such as PRONATURA, ROC, NIPARAJÁ, and fishing reserves leaders; and other members co-founders of Marine Conservation in Mexico as Alumbra Innovations Foundation.

Jointly with Loreto National Park ranger, the fisheries officer (CONAPESCA) inspected a fisherman and explained to them about the marine zones that they are allowed to fish in and not fish in. Education for the public (without jumping to quick judgement) is incredibly important for building understanding and trust with local communities.

GC is fostering strong collaboration with National Park authorities, Community Fisheries, law enforcement agencies, NGO partners, and community leaders. GC is supporting the creation of new national parks and community fishing refuges, as well as enhancing the training of marine wardens and community guardians to ensure effective enforcement.

Global Conservation works at a landscape scale in the Baja Sur Marine Corridor (BSMC) to improve compliance and marine protection at a regional level:

Loreto Bay National Park

Espiritu Santo National Park

‘Refugios Pesqueros” – Agua Verde + 4

San Basilio Bay

East Cape - Boca del Álamo

Photo ©adobestock

Baja Sur Marine Corridor (BSMC) encompasses an area of approximately 27,200 square kilometers, but only a mere 21,300 hectares of this area is currently designated as a "No Take" zone, encompassing 7.8% of the total area.

GC is collaborating with the National Fishing Authority (CONAPESCA) and National Parks (CONANP) to establish a new Pericu National Park focused on the San José Archipelago just north of La Paz, an ideal area for marine tourism.

IUU fishing and overfishing have led to the collapse of many species along this area, including the disappearance of keystone species such as hammerhead sharks and grouper in this region. The loss of megafauna is directly impacting the entire scuba industry and leading to the closure of numerous dive operations.

The Baja Sur Marine Corridor (BSMC) is of critical importance for communities and local fisheries and global megafauna that breed in the Sea of Cortez. Baja Sur communities depend on healthy marine ecosystems for their livelihoods and economies. For this reason, GC works to build capacities in coastal communities and marine protected areas.

The M3 Radar is a mobile radar that can be transported to different areas for protection across the marine protected area.

Global Conservation Leads Anti-Poaching Compliance Initiative

On the eastern coast of Baja California Sur, Global Conservation, with the support of local partners and donors, has successfully deployed three M2 Marine Monitors across the San Basilio Bay, Bahía de Loreto National Park and through the Loreto/La Paz marine corridor (the first Marine Monitor Mobile), near the fishing refuges, including communnities such as Agua Verde and San Cosme.

Working in partnership with CONAPESCA, who are responsible for designing and managing public policies on fisheries and aquaculture, GC engages with local citizens who become Community Gaurdians in an effort to protect their natural resources. Meetings like this one reveal information about recent poaching activities.

GC Projects Director of these areas, Alejandro González, is spearheading initiatives to work with local communities to protect the biodiversity found in the stunning underwater ecosystems of Mexico. And by working with private landowners, they can place mobile M3 radar stations to survey for poachers in protected marine areas. The private landowners will also engage with other communities to spread the word about good fishing practices to prevent fishermen from fishing in the wrong areas and prevent bycatch.

Mobula rays face challenges from both high-seas fisheries and entanglement. Manta rays cannot swim backwards and must constantly swim forward to transfer water over their gills, hence they are frequently caught and imprisoned in fishing and mooring lines. When the line snags on their body, gill slits, jaws, or cephalic fins, they execute backward rolls and turns in an attempt to free themselves. Unfortunately, this frequently leads to additional complications.

As part of our Global Marine Parks Defense, we have strategically installed an innovative, technological tool that acts as a fully off-grid autonomous system which facilitates remote surveillance, understanding nautical activities, detecting illegal fishing, and recreational activities in the southern area of the Bahía de Loreto National Park, the fishing refuges, and the remote islands of the protected area.

The M3 allows the detection and recording of nearby vessels with a high degree of accuracy throughout tracks that contain information such as duration and position over time through an integrated radar/long range camera system and AIS signals. Additionally, it generates data such as images of vessels entering its range and loitering patterns. With an off-grid power system and real-time data transmission, its main advantage is strategic mobility, as well as enabling remote monitoring for a variety of users, authorities, and community guardians.

This tool has proven to be not only a technological advantage, enabling us to comprehend nautical and fishing activity in the southern part of the National Park, but also a valuable instrument for the fishing surveillance committees of the cooperatives based in Agua Verde and San Cosme communities. These committees have expressed interest in expanding their monitoring capabilities by incorporating such tools into their network of fishing refuges.

Turtle egg poaching is also a concern for GC’s authorities. It’s not only the water that’s protected, but the land as well. Daily patrolling across multiple protected areas guarded by GC reveals the extent of poachers efforts.

By comparing the level of information provided by vessel tracking platforms such as Skylight and/or Global Fishing Watch, it is possible to understand at a regional level how marine activity is connected and impacted along the corridor from Loreto to Espiritu Santo Island, recognizing that the southern area of the Bahía de Loreto National Park is a key point for the fishing communities within its area of influence.

The M2/M3 radars are capable of capturing live images of vessels a few miles out form the coastline.

We have also gained insight into fishing activities that occur both inside and outside the protected natural area, as well as within two of the largest fishing refuges in Mexico, to assist the authorities in conducting EarthRanger and SMART patrols. We can confirm that the level of detail in the southern part of the National Park surpasses those platforms, primarily due to the M3's ability to detect all types of vessel activity through radar, AIS, and camera. This represents a superior level of detail when it comes to identifying specific vessels or recording those that are regularly present in the area.

Jointly with Loreto National Park ranger, the fisheries officer (CONAPESCA) inspected a fisherman and explained to them about the marine zones that they are allowed to fish in and not fish in. Education for the public (without jumping to quick judgement) is incredibly important for building understanding and trust with local communities.

The Mobile Marine Monitor, supported by park rangers at Bahía de Loreto National Park, fisheries officials, and local partners, is a powerful tool for collecting information on vessel loitering, identifying potential areas of interest through heat maps (illegal fishing), identifying legal fisherman and boats, establishing peak activity times and days, and supplementing knowledge of activities in the area. It also allows us to interact with new interested users, such as legal and organized fishers from the villages surrounding the National Park, and start a discourse about potential collaborations.

Patrolling marine protected areas means surveying the open waters, coastlines, and the land itself, including the many islands of Baja Sur and the Gulf of California.

Patrolling, though, is potentially dangerous. Cartels often fund poaching looking for specific species that are valuable on the black market, like critically endangered totoaba, fish that are valuable because of their bladders which are used in fake Chinese medicines. Projects Director Alejandro looks to partner with the Mexican Navy, Police, and other governmental officers to protect the GC team, rangers, and officers from poachers while on patrol.

Just a few weeks before writing this, North of our project areas, two officers were kidnapped and another murdered. Although not part of GC, anticipating possibly lethal changes coming to our project areas, it is essential to partner with governmental entities for protection.

Fishermen must acquire a permit for fishing and only in specific zones. When poachers are caught, if their catches are still alive, like the brown clams pictured above, they will be forced to release them back into the wild while under the supervision of our officers. Then, of course, they are warned and/or fined.

As ever, Global Conservation stays motivated to halt poaching in Mexico.