Mirador National Park, Guatemala

OVERVIEW

This is the Heart of the Maya Biosphere and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Mirador National Park, a proposed 500,000-hectare protected area, contains the largest intact primary forest and wildlife habitat in Central America with over 40 major ancient Maya cities and interconnected causeways.

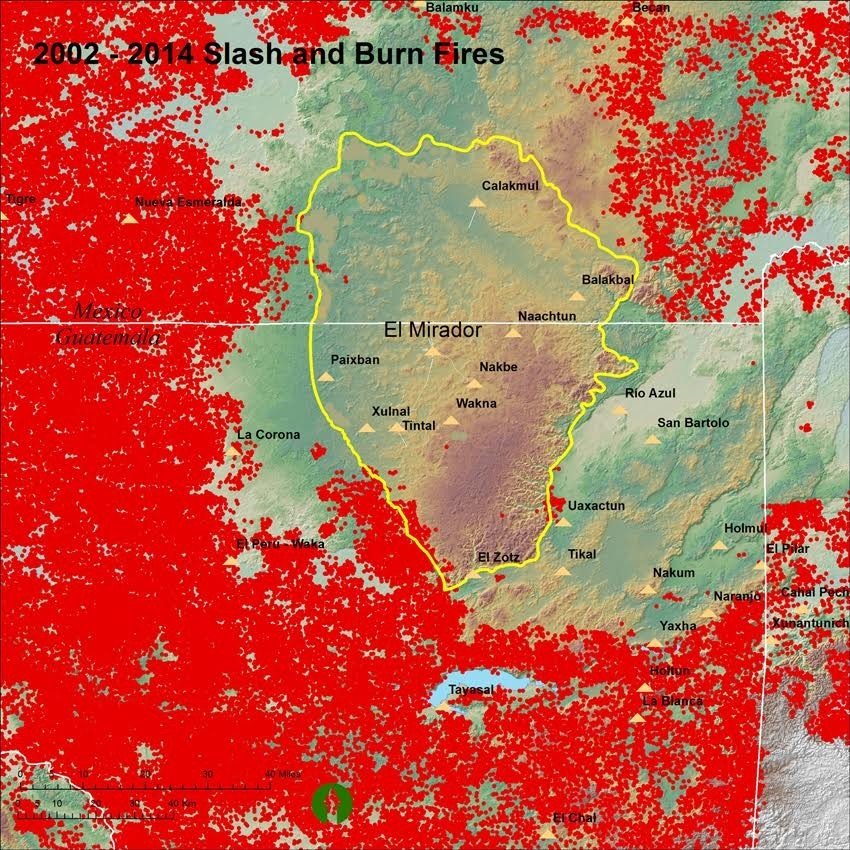

The Maya Biosphere is losing an average of 50,000 hectares a year to fires and clearing of the surrounding Maya Biosphere Reserve, driven by drug trafficking and cattle ranching.

SIZE

500,000 Hectares

GOAL

$780,000

VISITORS BY 2030

9,000

Introduction

Two and a half thousand years ago, one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world thrived in Central America. The Maya were known for their art, architecture, mathematics, calendar, and the most sophisticated writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. With this knowledge, they built massive cities containing some of the largest structures ever built in ancient times, connected by complex road networks.

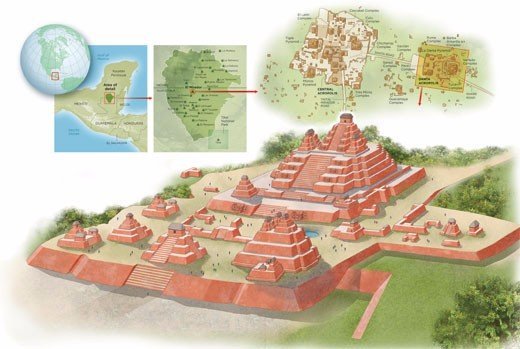

The Mirador region, covering more than 1.6 million acres in northern Guatemala and southern Campeche, Mexico, contained an integrated cultural and natural system enclosed by limestone hills hundreds of meters high. There, in an ancient city called El Mirador, more than 200,000 Maya thrived on perennial swamps. They used the nutrient-rich mud from the swamps for agricultural terraces, constructed by the thousands throughout the area.

Now, these sprawling metropolises have been reclaimed by rainforest, the trees enshrouding great cultural treasures and an ark of endangered species. What once was the cradle of an extensive Maya civilization is now the largest intact forest and wildlife habitat remaining in Central America. Hidden in the depths of this verdant rainforest are over 80 ancient Maya cities, containing elaborate temples and some of the largest pyramids on earth. These massive structures are at least a millennium older than other well-known Maya cities such as Tikal, Palenque, Copan, or Chichen Itza. Just beneath tree roots that wind through the thick black soil are hundreds of miles of ancient plastered roads paved with white lime cement, connecting an area larger than Puerto Rico.

Cultural Heritage

At El Mirador, the Maya built the most voluminous pyramid in the world, called La Danta. At 2.8 million cubic meters (more than 1,100 Olympic swimming pools), 70 meters high, and with a base the size of 35 football fields, it took up to an estimated 15 million man days of labor to construct. The pilots who first observed La Danta and its neighbors in the 1930’s initially believed these pyramids to be volcanoes poking through the forest canopy.

Natural Heritage

In addition to its cultural treasures, this part of Guatemala is also biologically rich. Large populations of elusive jaguar and threatened white-lipped peccary live here, alongside pumas, tapirs, ocelots, agoutis, brocket deer, and rare harpy eagles. Mirador's southern limestone cliffs are the last place in the world with viable populations of the orange-breasted falcon. Mirador is also on a critical flyway for birds migrating from central and eastern North America.

The Mirador area contains six kinds of tropical forest, 300 tree species, 200 animal species, and five of the six cats indigenous to Central America.

Threats to the Cradle of Maya Civilization

The ancient city of El Mirador has been partially protected since 1990 by the small Mirador-Río Azul National Park, part of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, more than 2 million hectares of rainforest in northern Guatemala. The park protects a narrow strip of forest along the Mexico border, and only three of the dozens of ancient Mayan cities that are currently known in this area. However, nearly half of that area has now been permanently destroyed. In addition to logging, the park is threatened by construction of access roads, poaching, illegal agriculture, ranching, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and looting of archaeological sites.

Although the Maya Biosphere Reserve covers an impressive 10% of Guatemala’s total land area, almost 50,000 hectares of forest (about nine times the area of Manhattan) are lost each year in this reserve to agriculture and cattle ranching. In just the past 10 years, more than 60% of the Maya Biosphere Reserve’s forests have been destroyed.

Saving Mirador – Heart of the Maya Biosphere

To fight these threats, Global Conservation has collaborated with our partners FundaEco, Rainforest Trust, and FARES to establish the first Mirador Park Authority. These rangers work with the Guatemalan government and local communities to achieve “No Cut, No Kill” protection of forests and wildlife. Their patrols now cover 40 ancient Maya cities and over 300,000 hectares of tropical rainforests. Global Conservation has also deployed a Global Park Defense system including ranger patrols, cellular trailcam networks, facial recognition software, command and control systems, satellite monitoring, and community involvement.

We are also supporting critical tourism and park infrastructure including year-round trails, safety and security, and communication systems. Nearby communities are shifting from extraction industries to sustainable ecotourism, improving their living conditions without resorting to illegal activities. The Community Eco-Guard program offers local residents, who might otherwise make a living hunting or logging, an ecotourism-based livelihood.

Further, Global Conservation is committed to achieving UNESCO World Heritage designation for Mirador National Park while securing key forestry concessions to expand the protected area. Based on our work with the Guatemalan private sector and multiple governments over the past decade, we are now in a unique position to realize the permanent protection of Mirador National Park. Soon, we will achieve the establishment of the first Wilderness Area in Latin America, the Mirador-Calakmul Cultural and Natural Sanctuary.

Beyond protecting Mirador’s natural treasures, Global Conservation is also supporting cultural heritage protection. Working with the Foundation for Anthropological Research and Environmental Studies led by Dr. Richard Hansen, we have raised over $3 million in country from Guatemalan businesses and families for the preservation of El Mirador’s legacy.

Our Objectives:

1.

Establish permanent legal protection for the nature, wildlife and archaeological heritage of Mirador.

2.

Assist the Guatemalan government in securing UNESCO World Heritage designation.

3.

Negotiate trade-offs with stakeholders that will determine which lands will be integrated into the new, larger national park.

4.

Secure larger international support for park set-up after initial five-year startup operations.

5.

Achieve an economically sustainable protected area within the next ten years, ie. tourism revenues exceed park operating costs.

Critical Initiatives:

Global Conservation is sponsoring three critical initiatives in 2020-2024

Establishing the Mirador Park Authority

Working in close collaboration with the Guatemalan government's Consejo National de Areas Protegidas (CONAP), the Instituto Guatemalteco de Turismo (INGUAT) and local communities, we will organize a professional ranger force and park management. Mirador Park Authority integrates existing guards, experts from Tikal National Park, and local NGOs to protect Mirador National Park.

SMART Ranger Patrols

Provide wildlife anti-poaching training, equipment, rations and technical support to Mirador National Park rangers to implement SMART patrols, increasing coverage, accountability and interdictions of illegal activities.

Habitat Acquisition and New Protection for Core Wildlife Areas

There are highly important areas for wildlife habitat in Mirador. Funding land acquisitions and implementing protection networks for these core areas is the highest priority.

The new president of Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, is championing Mirador National Park with UNESCO World Heritage and the Vice President recently spoke at Paris COP21. The next 4 years is a critical time for Mirador’s long-term protection and sustainable development.

The Opportunity – Sustainable Tourism and Conservation

Nearby Tikal National Park generates over 38,000 jobs and $220 million in tourism income every year, comprising 4-6% of Guatmala's economy. Mirador contains at least 12 ancient Maya cities that are even larger and more than a thousand years older than those in Tikal, with the potential to attract even more tourism. Within 10 years, sustainable tourism revenues from Mirador should pay for park management and protection. Visitation to its amazing cities, pyramids and temples has already grown to over 3,000 visitors per year, generating over $1.5 million in tourism revenues for local communities.

With projected tourism into Mirador expected to grow to over 10,000 visitors a year by 2020, a relatively small investment in conservation and park setup will enable Mirador to achieve sustainable park operations with on-going funding for long-term wildlife and cultural heritage conservation. Already, over 350 Guatemalans are directly employed in Mirador and thousands benefit from tourism, working as business owners, guides, cooks, transport and suppliers for the 5-6 day round trip adventure. The communities are benefiting from new water supplies, schools, solar energy and educational resources never previously available in the region.

Our goal is to establish sustainable tourism in Mirador with active local community involvement to provide economic alternatives to destructive activities (e.g. illegal logging, archaeological looting, and human, wildlife and drug trafficking).

Global Conservation is dedicated to ensuring that Mirador tourism is responsible and sustainable, and that local communities benefit directly. As part of this initiative, the Guatemalan government has agreed to improve the road to the villages surrounding Mirador, provide increased security measures for tourists, and supply electricity for rural villages surrounding Mirador for the first time.

To ensure that Mirador itself remains a road-less wilderness sanctuary, Global Conservation is conducting a feasibility study for a narrow-gauge, propane-driven rail system that will transport visitors into this area and between major archeological sites. Not only will the rail restrict noise and pollution, it will also allow the Mirador’s management to strictly control visitor flow, leaving key wildlife habitat undisturbed. Opportunities for hiking or horseback riding will continue to be available, offering the same visitor experience that is available today.

Community Development

Global Conservation is working with our partners and local communities to provide new educational and economic alternatives to practices that wreak havoc on the environment, the archaeological sites and individual families in and around Mirador.

"It is tremendously gratifying to see the achievements of local people who traditionally have had so little hope. The opportunities provided by the Mirador Project are a major advantage for the protection and preservation of the area, and are a real solution to many of the problems facing Guatemala and the communities living adjacent to Mirador." - Global Conservation Executive Director Jeff Morgan

Employment. The project contributes directly and indirectly to the communities adjacent to Mirador by contracting more than 320 workers. Labor recruitment also extends to other parts of the Peten. More than 35 workers are highly trained Maya masons and consolidation experts from Coban, Alta Verapaz. Additional services are contracted during field seasons for muleteers, cooks, guides and kitchen assistants. The scientific/technical team includes more than 40 people. To accommodate this work force, FARES has established multiple camps with year-round water supplies through a major cistern.

Basic Education. The Mirador Project provides trained teachers for the communities of Carmelita, Cruce a la Colorada and Dos Aguadas, with computer-based classes taught in Carmelita to 5-60 children from 2nd through 6th grades.

Literacy Training. The Mirador Project provides literacy courses to 141 workmen, with the majority learning to read and write their names, read elementary texts, and to read and write numbers. Math courses are also given for basic home and business financial calculations. In addition, the Project provides educational classes in the evening to all 320 Mirador employees on subjects ranging from history, ecology, financial consulting, hygiene, health and first aid, archaeology, photography, ethnohistory, investment strategies, botany, and biology.

Species Facing Extinction

In Mirador National Park, we are working with our partners to protect the jaguar.

Global Conservation is funding a multi-year Species Population Baseline study in collaboration with Dr. Gerardo Ceballos for jaguars to ascertain progress in Park and Wildlife Protection from our investments in Global Park Defense in Mirador.

Only 1,200 jaguars remain in Mirador National Park, one of the species' strongholds. The jaguar is the largest feline in the Americas, a valuable component of the ecosystem as a top predator and an iconic symbol of South American culture.

Conclusion

What happened to the ancient Maya that once ruled these forests? Two thousand years ago, their civilization collapsed in the wake of ecological disaster. The swamps that supported Mayan farms with their nutrient-rich mud were buried by clay runoff caused by wholesale deforestation of the surrounding area. The Maya had been destroying the forest for firewood to make lime cement to decorate their plazas and pyramids, an extravagance that eventually led to their own demise. We aim to preserve El Mirador’s history but not to repeat it, instead conserving Mirador’s forests and wetlands in perpetuity.

Partners in Conservation

Foundation for Anthropological Research and Environmental Studies (FARES)

Dr. Richard Hansen is a world-renowned archaeologist and conservationist who has championed the protection and responsible development of Mirador for over 25 years. He is the founder and president of the Foundation for Anthropological Research and Environmental Studies (FARES).

Previously, he was Senior Scientist at the Institute for Mesoamerican Research in the Department of Anthropology at Idaho State University. His work is regularly featured in documentary films, including on the Learning Channel, the Discovery Channel, ABC's 20/20, 60 Minutes Australia, ABC’s Good Morning America, ABC’s Primetime Live, CNN International Untold Stories, CNN Global Challenges, The History Channel, British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Guatevison, and in multiple National Geographic films.

FundaEco is a private nonprofit dedicated to the creation, management, protection and conservation of Guatemala's protected areas. It has spent the past 25 years helping communities find socioeconomic alternatives to destructive land uses.

Rainforest Trust is a global nonprofit that was started 30 years ago to purchase and protect tracts of threatened rainforest. They have already protected almost 10 million hectares (23 million acres) of rainforest, and are looking to secure more than double that for a total of more than 20 million hectares (50 million acres).